We are currently watching a weird evolution in software development. We have “No-Code” developers and “Pro-Code” engineers, but the lines are blurring into a messy middle ground where everyone is just… prompting.

The problem isn’t that people are using AI to write code. The problem is how they are doing it. It’s chaotic. It’s a stream of consciousness typed into a chat window. There are no guardrails. There is no structure. We are trying to build skyscrapers by shouting vague instructions at a very fast, very eager, but slightly hallucinating contractor.

This lack of structure bothered me. So, I decided to do something about it.

I spent a weekend of hyperfocus building Intend—an experimental programming language designed to bridge the gap between human intent and machine implementation.

I didn’t build this alone. I built it with Gemini. And I don’t mean “I asked Gemini to write it for me”.

This was a 50/50 partnership. I was the Architect; Gemini was the Contractor. I designed the AST, defined the constraints, and debugged the logic. Gemini wrote the parser boilerplate, suggested patterns, and—frequently—broke things in creative ways that forced me to rethink my design. It wasn’t magic. It was engineering.

The Philosophy: Prompting with Seatbelts

The core hypothesis was simple: Prompts shouldn’t be wishes; they should be specifications.

I wanted to invert the workflow. I wanted a language where the human defines the boundaries—the types, the safety checks, the “what must be true”—and leaves the “how” entirely to the AI.

The Architecture of a Hallucination

To test this, we built a compiler.

We created a file extension, .intent. The goal was to give the AI “Hollow Context”—feeding it only the shapes of data (interfaces, types) without distracting it with the implementation details of the entire codebase.

1. The Syntax (The Guardrails)

We didn’t just regex the text files. We used Chevrotain to build a real parser that generated an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST).

Why go through the pain of writing a lexer for a fake language? Because we needed to semantically separate Safety from Logic.

Here is what real Intend code looks like. It replaces function bodies with natural language steps, but keeps the strict typing of TypeScript. Crucially, it allows Direct Function Calls—mixing AI fuzziness with deterministic code execution.

By parsing this into an AST, we could construct what I called “Smart Prompts”. We injected the invariant block at the very top of the context window, telling the model: “If you violate these rules, the compiler will reject you.”

2. From CAS to Lockfiles (The Quest for Determinism)

The biggest problem with AI is that it’s a slot machine. You pull the lever (run the prompt), and you get a different result every time.

Attempt 1: Simple Caching At first, I just implemented a crude “Content Addressable Storage” (CAS). I hashed the input prompt. If the hash matched, I returned the previous output. Problem: It wasn’t enough. If I changed the model temperature in the config, the hash stayed the same, but the output should have changed.

Attempt 2: The Lockfile

I realized we needed something like package-lock.json. We needed a source of truth that froze the hallucinations in time.

We built a system that hashed:

- The Source Code of the

.intentfile. - The Configuration (Model provided, Temperature, TopP).

If these hashes matched an entry in intend.lock, we skipped the AI entirely. We just hydrated the build/ folder with the cached TypeScript code.

This meant that intend build on my machine produced the exact same binary as intend build on CI. The stochastic nature of the LLM was tamed—until you edited the file.

3. The “Self-Healing” Loop (A.K.A. The Infinite Loop of Doom)

This was the feature I was most excited about. And it was the feature that broke my spirit.

The idea was simple:

- Generate code from

.intent. - Run strict TypeScript validation on the output.

- If it fails, feed the error back into the prompt and ask the AI to fix it.

In theory, this is “Agentic Coding.” In practice, it was “Agentic Whack-a-Mole.”

We ran into a recurring nightmare where the model would fix a type error, but in doing so, it would:

- Re-implement imports: Instead of using the

hash()function I imported, it would write its own (buggy) hashing logic inline. - Hallucinate APIs: “Oh,

UserSchemadoesn’t have anid? Let me just add one to the interface definition.” (No! You can’t change the interface! That’s the one thing you can’t change!) - The Loop: It would fix error A, causing error B. It would fix error B, causing error A. I sat there watching the terminal spin for 5 minutes, burning tokens, only to crash with

MaxRetriesExceeded.

4. The Structure

We didn’t want a “magic folder” that hid everything. We wanted a structure that felt native to a TypeScript developer. An Intend project looks suspiciously normal:

my-app/

├── intend.config.json // Provider settings (Gemini/Ollama)

├── intend.lock // The "frozen" hallucinations

├── src/

│ ├── types.ts // Standard TS interfaces (The "Hollow Context")

│ └── main.intent // The hybrid AI/Code source

└── out/ // The compiled, strict TypeScriptYou write in src/, you commit intend.lock, and you deploy out/. It’s boring, and that was the point.

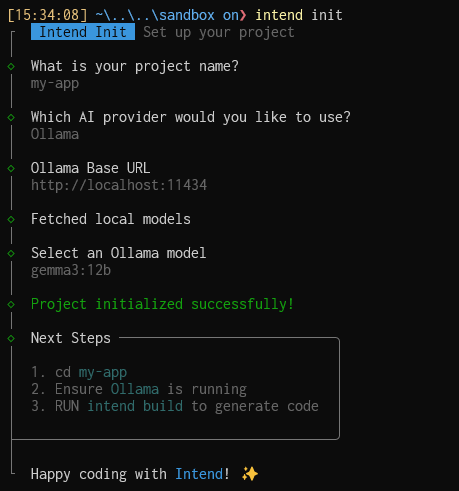

4. The Experience (Pluggable Brains & Shiny CLI)

We didn’t just build a compiler; we built a product.

We wanted this to feel like a premium developer tool, not a Python script hacking together API calls. We support Gemini (for speed and reasoning depth) and Ollama (for local, privacy-focused coding) out of the box.

We also spent way too much time on the CLI. It features a beautiful, interactive interface (built with @clack/prompts) that visualizes the “thinking” process of the compiler:

The Reality Check (Why We Shelved It)

On paper, Intend is the perfect bridge for the future of programming. But after the weekend fever dream wore off, we hit the wall:

1. The “Local” Deception

I wanted this to run on developers’ machines using local models (like ollama/gemma3:12b or llama3). I didn’t want to pay Google for every compile.

The Result: Small models are terrible at following negative constraints. They would look at “Do not re-implement hashFunction” and immediately re-implement it. They lacked the “reasoning” depth to hold the entire AST context in memory without hallucinations.

2. Latency is the Flow Killer

A standard compiler runs in milliseconds. Intend, even with caching, ran in seconds (or minutes on a cache miss).

Waiting 45 seconds to see if your if statement logic is correct effectively destroys the “Flow State.” You can’t iterate. You start checking Twitter while your code compiles. That is death for productivity.

3. Fragility

Traditional code breaks when you make a logic error. Intend code broke because the model “felt different” that day. We found that even with temperature: 0, floating point determinism across different GPUs meant that sometimes, the code just… broke.

What’s Next? (Or, How to Fix It)

Intend was a successful failure. It proved that while we can wrap AI in the skin of a programming language, the underlying engine isn’t quite rigid enough to act as a compiler. Attempting to force a creative, probabilistic engine into a deterministic, strict pipeline is fighting physics.

However, the dream isn’t dead. Here is how I would build Intend v2:

- Two-Way Editing (Ejection): Instead of

intent -> ts, we should allow the user to edit the generated TS files and have those changes reflect back (or at least “eject” from the AI flow entirely). - Better Negative Constraints: We need smarter prompting strategies (like Chain-of-Thought) to stop models from re-implementing imports or hallucinating APIs.

- Hybrid Orchestration: Leaning even harder into “Direct Function Calls”—letting the AI handle only the fuzzy logic (like sentiment analysis) while strict code handles the payments.

For now, I’m back to writing TypeScript manually. But the idea of “Architecting Constraints” rather than “Writing Syntax” hasn’t left my mind.

We might just be a few years (or a few model generations) too early.

Resources

The project is open source and published on NPM. You can try the chaos yourself:

- Documentation: intend.fly.dev

- NPM:

@intend-it/cli,@intend-it/parser,@intend-it/core - GitHub: github.com/DRFR0ST/intend

Just don’t try to run it in production. Please.